Implications of Waters of the U.S. (WOTUS) for local governments

This is the first article in a series written by SSDN’s Environmental Finance Center staff. These centers exist to help communities navigate the complex world of federal funding.

By Catherine Mercier-Baggett, Director of Federal Technical Assistance

One fundamental lesson public servants learn is the importance of defining words and terms. What is a “household”? Is it a family, composed of individuals related through kinship? Is it a group of people who cohabitate, regardless of what brought them together? These questions were at the heart one of the very first zoning cases heard by the U.S. Supreme Court, Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. (1926) and continue to be debated to this day.

The ramifications of defining “Waters of the United States,” aka WOTUS, run just as deep and have generated various court rulings since the ratification of the Clean Water Act in 1972. After a succession of court cases and reversals in the WOTUS definition, how to define “relatively permanent” and “continuous surface connection” of wetlands remains unresolved.

For professionals without a background in environmental law who must implement and enforce these definitions on a daily basis, it can be difficult to understand the potential impacts of a change.

In November, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Department of the Army (Corps of Engineers) put forth a new rule that would narrow what is defined as WOTUS. The proposed definition would impact several sections of the Clean Water Act as outlined in the Regulatory Impact Analysis for the Proposed Updated Definition of Waters of the United States Rule prepared by EPA and the U.S. Army.

The intent is to provide clarity, consistency, and predictability, and it would effectively reduce the number of streams, lakes, and wetlands considered jurisdictional waters, and consequently the number of permits to be reviewed and issued by EPA and USACE.

Potential impacts for local governments

With a reduction in the number of waterways and wetlands subject to WOTUS, local and regional governments can anticipate the need to adapt some of their approaches to wetland delineation, water sampling, project funding, and construction permitting.

Wetland delineation

To qualify as WOTUS, bodies of water would need to have flowing or standing water for at least the duration of the wet season. This means that each region, based on historical data, will need to determine the extent of their wet season, and ensure delineation activities happen during that period of time.

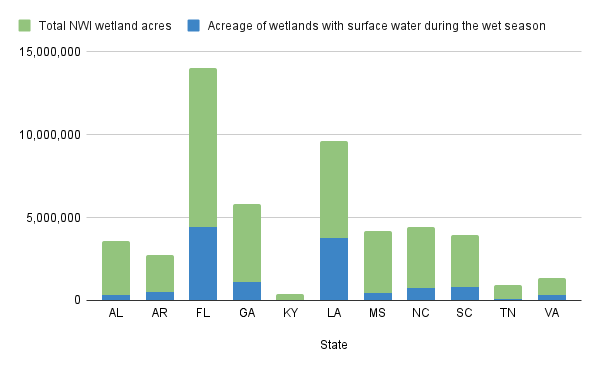

The National Wetlands Inventory is a dataset of potential wetland areas, identified by satellite imagery. It was not designed for regulatory purposes as field verification is always required. However, it is the most comprehensive information available at the national level. According to the Regulatory Impact Analysis, 19% of the wetlands currently mapped on the National Wetlands Inventory (NWI) would meet the wet season criterion. In the Southeast, a region with an intricate coastline and expansive marshes, about one-third of the 38.4M acres of wetlands in the NWI are likely to be considered relatively permanent.

In addition to the relative permanency criterion, wetlands that are not directly connected to a jurisdictional water (for example those fed exclusively by groundwater) would not be considered WOTUS. The analysis of the NWI does not take into consideration the connectivity of wetlands to jurisdictional waterways. Consequently, the actual proportion of wetlands meeting the full definition of WOTUS is expected to be lower than illustrated below.

Water sampling

The Total Maximum Daily Loads, the quality standards established through Clean Water Act Section 303, may no longer apply to certain waterways and result in less required water quality samplings. Because the results provide information on what is being discharged in the water by adjacent land uses, sources of pollution may become more challenging to identify.

Funding – mitigation banking

Certain projects subject to the Clean Water Act Section 404 may be required to offset adverse environmental impacts to fragile ecosystems such as wetlands by purchasing credits that are used to fund rehabilitation and conservation of a different area deemed equivalent to the one impacted. Market-driven restoration efforts may be impacted by a lower demand and availability of credits, possibly leading to less restoration projects and more expensive credits. Cities and counties that count on mitigation banking would need to consider alternative sources to fund projects on receiving public land that would no longer be categorized as WOTUS and lose their credit value.

Funding – Clean Water programs

By changing what qualifies as WOTUS, some projects such as streambank improvements on tributaries that are no longer WOTUS may become ineligible for the Clean Water State Revolving Fund and the Section 319 Nonpoint Source Pollution. The intent of both programs is to safeguard the integrity of water resources and the health of communities that depend on them.

Many local and regional capital improvement projects are supported by federal funding through the State Revolving Funds. These low-cost loans issued and managed by the states are meant to support improvements to water infrastructure such as the modernization of a wastewater reclamation facility. Similarly, the Section 319 pass-through grants address water quality but from nonpoint source pollution. Both programs have been used extensively to support green stormwater infrastructure.

Construction permitting

The definition change would likely reduce the proportion of construction projects that are subject to National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permits under Clean Water Act Section 402. Many states and local entities are authorized to control the discharge of pollutants in waterways by administering the NPDES.

State and local legislation

States, municipalities where state law allows , and Tribes would continue to have the ability to impose more stringent standards if they choose, and regulate more water bodies that would fall outside federal purview. The Regulatory Impact Analysis reports that nearly half of the states already adopted regulations broader than the proposed rule, including Arkansas, Florida, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia.

Local governments could prepare by reviewing their local ordinances, watershed planning documents, and capital improvement projects priorities to determine how the adoption of the new rule would affect their activities.

For more information

Please note that SSDN does not necessarily support or endorse the views and opinions expressed in the articles listed below.

EPA, Frequent Questions on the WOTUS Proposed Rule: Basic information on the proposed rule

SWCA, Ten Things to Know About the Proposed 2025 WOTUS Rule: Brief impact analysis of the proposed rule

Farm Bureau, WOTUS and the American Farmer: Impact analysis from an agricultural perspective

ESA Associates, Proposed Update to Definition of WOTUS: Impact analysis with project scenarios

Interested parties can find detailed information on the proposed rule, read public comments and submit their input on the eRulemaking Initiative website. The 45-day comment period on the proposed rule closes Jan.5, 2026.